Course Content

Childhood Asthma: Prevention and Treatment

Course Content (Viewing Only)

Introduction to Asthma

One in 13 people are directly affected by asthma (5). Asthma is a chronic disease of the lungs that causes wheezing, coughing, difficulty breathing, and chest tightness (9). For patients with asthma a common cold or allergic rhinitis can quickly escalate into a life-threatening event. Triggers in the environment can quickly initiate trouble among delicate, inflammation prone, airways.

Although asthma is one of the most prevalent chronic diseases among adults and children, it is often not well controlled. While many patients know that they have asthma, many do not know how to manage it to prevent exacerbations. This can be especially devastating in children as their daily schedules, sleep, education, and activities can be significantly altered by uncontrolled asthma.

Educating and empowering patients and their families to prevent disease exacerbation is a key component of successful asthma treatment. We will discuss asthma prevalence, common triggers, signs of asthma exacerbations, and prevention strategies in this course.

What is Asthma?

Asthma is a chronic disorder of the respiratory system that is characterized by four primary components: recurrent respiratory symptoms, bronchial hyper-responsiveness, airway obstruction, and inflammation (9).

Certain factors such as genetics, environment, socioeconomic status, smoking status, and race/ethnicity can increase the chances of developing asthma. Common triggers of asthma include allergens, pollution, cold air, stress, and exercise, among other irritants.

Environmental factors trigger dendritic cells, which produce B and T cell lymphocytes, initiate IgE production of mast cells, eosinophil, and neutrophils. The end result of this cascade is bronchial inflammation.

These cells also activate Th2/Th1 cytokines which amplify the response of the smooth muscle walls leading to persistent inflammation and remodeling of the tissues (long-term) (9).

Airway Remodeling in Asthma

When bronchoconstriction and airway inflammation are persistent airway edema occurs, worsening asthma symptoms. Airway edema can continue to exacerbate symptoms by promoting increased mucus production, mucous plugging, and hypertrophy and hyperplasia of the smooth muscles.

The combination of bronchoconstriction and airway inflammation gives rise to the chronic symptoms of coughing, wheezing, and difficulty breathing.

This is known as airway remodeling and this process makes asthma treatment more complicated as many commonly prescribed medications have limited response on altered bronchial tissues (9).

Importance of Early Diagnosis and Management

While asthma cannot directly be cured, it can be managed. The earlier asthma is diagnosed, the earlier prevention education can be provided, and the earlier pharmacological management initiated, if indicated.

The primary goal in asthma therapy is to prevent and reduce chronic inflammation (which leads to airway remodeling) and acute exacerbations.

Proper management of asthma symptoms helps to reduce chronic damage by way of airway remodeling while reducing the odds of death related to an asthma attack and increasing quality of life.

Learner exercise

Why is early diagnosis of asthma key in management?

What are some of the difficulties in diagnosing asthma in young children?

Prevalence and Impact of Pediatric Asthma

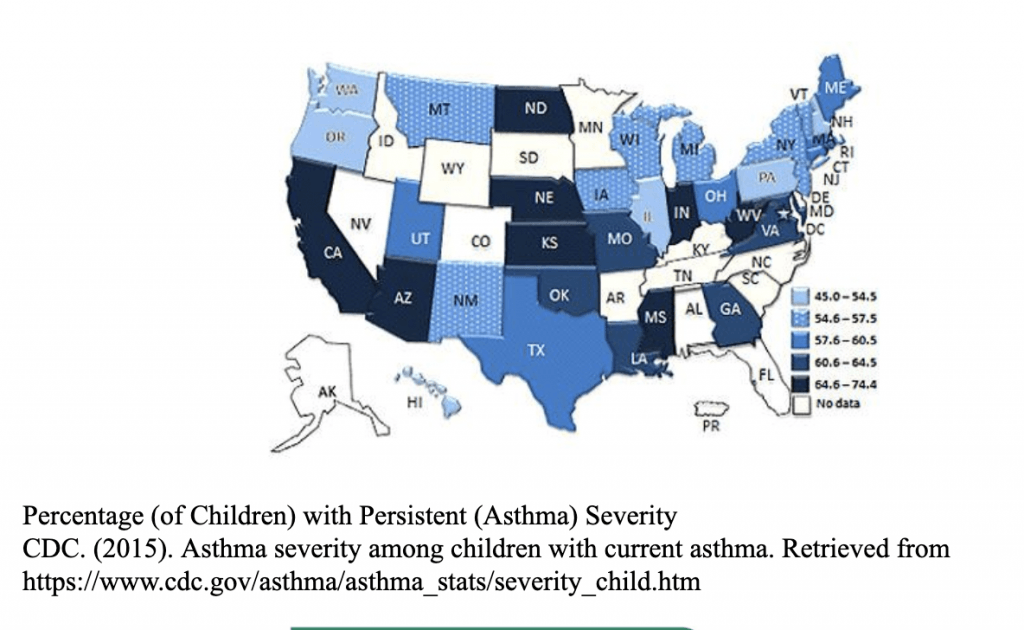

Below are statistics of asthma prevalence in children from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s National Health Interview Survey (NHIS) (3,5,6,9):

• Approximately 6,000,000 children in the United States have been diagnosed with asthma.

• 50-80% of children with asthma develop symptoms before their fifth birthday.

• Approximately 1 in 10 school-age children have asthma.

• Approximately 50% of children with asthma have reported having asthma exacerbations and/or having poor control of their asthma within the past year.

• 10.5 million school days are missed every year due to asthma symptoms.

• ⅓ of hospitalizations in children under the age of 15 are related to asthma.

• In 2016, 209 children died from asthma related illness.

Presentation and Risk Factors

Children can be diagnosed with asthma at a very young age. These children usually present with symptoms of persistent allergy, cough, and intermittent wheeze (6). They often present to the primary care office or emergency department with asthma symptoms during periods of increased allergen exposure and/or a viral respiratory illness.

Respiratory viruses attack airway structures causing inflammation and increased mucus production which exacerbate asthma symptoms. Children with asthma symptoms prior to the age of 3 have been seen to have significant lung growth deficits by age 6 (9). Early diagnosis and treatments are critical in reducing such complications.

Gender is a risk factor for asthma development. In early childhood, boys are more likely to have asthmatic symptoms. Later after puberty, that risk flips and girls more commonly have asthmatic symptoms (12). Children of African American and Puerto Rican descent have higher risk than those of Caucasian or Hispanic backgrounds (8).

Children with obesity are more likely to have develop asthma (9). Finally, asthma is more prevalent in households with income <100% below the poverty line (12).

While all children with persistent respiratory symptoms should be flagged and followed for potential asthma disease work-up, clinicians should be aware of the risk factors and be vigilant in screening and diagnosing those patients.

Learner Exercise

What are some modifiable risk factors for the development of asthma in pediatrics?

How can you educate parents and caregivers on these?

Diagnosis and Treatment Disparities

In a survey completed by the CDC’s National Center for Health Statistics (NCHS), it was recorded that in 2016 only 71.1% of children with asthma had routine healthcare visits (12).

Access to healthcare, especially in many rural and poverty-stricken areas, is a national concern. Creating outreach programs in schools, primary care offices, and local hospitals may help maximize asthma screening and treatment for at-risk children.

It is critical that healthcare providers recognize these care disparities and work with local and national resources to increase screening and diagnosis.

Asthma Severity

Asthma diagnosis and exacerbations are ranked based on of severity of symptoms, control, and responsiveness to therapies. Severity is the “intrinsic intensity of the disease process” (9). It can be measured by incidence of symptoms without long-term therapy.

Control is “the degree to which the manifestations of asthma are minimized and goals of therapy are met” (9). Finally, responsiveness is how easily asthma symptoms (especially exacerbations) can be managed (9).

A combination of family and individual medical history, lung function testing, and history of asthma-related medication use help determine asthma diagnoses and treatment plans.

Patients with severe symptoms and a decreased response to therapy are at an increased risk for severe, life-threatening asthma attacks.

There are four classifications of asthma severity:

• Intermittent

• Persistent Mild

• Persistent Moderate

• Persistent Severe.

In children, components of severity are further separated by age group: 0-4 years, 5-11 years, and >12 years. Each level is described by the quantity of symptoms being experienced.

These symptoms include nighttime awakenings, need for short-acting beta2-antagonists (SABA) for quick relief of symptoms, work/school days missed, ability to engage in normal activities, and quality of life assessments (9).

Lung function testing with spirometry should be performed in a healthcare office to evaluate the child’s lung compliance. This test should be attempted in all children age 5 years old or greater if asthma diagnosis is being considered (9). Spirometry measures the child’s forced expiratory volume in 1 second and in 6 seconds (FEV1 and FEV6) and forced vital capacity (FVC).

Spiromerty should be performed before and after inhaling a SABA medication to help determine if there is airflow obstruction, its severity, and reversibility with use of a SABA (responsiveness) (9). The resulting numbers are compared to expected values for each age group and written as percentages.

Greater than 85% of expected lung compliance is considered normal for children up to age 19. Asthma severity and lung compliance are inversely related- the further the decrease in compliance the more severe the asthma is.

When combined with the child’s history of symptoms and medication use, healthcare providers can determine the classification of asthma severity and appropriate treatment measures using the stepwise approach. The stepwise approach helps to standardize asthma symptoms and initiate related therapies.

Healthcare providers use this information to determine when to move up or down a treatment level to provide the most effective management with the least number of exacerbations from this disease. Provider assessment of a child’s asthma maintenance therapy should be completed every 4-6 weeks with therapy changes and then every 3-6 months with good symptom control (8).

Learner exercise

Can a patient with well-controlled asthma experience a life-threatening attack?

Which patients are most at risk for severe asthma attacks?

Some patients have asthma which is not severe but is also not responsive to therapy. How would you categorically describe this?

Stepwise Approach for Classifying Asthma Severity

The chart below outlines the evaluation of asthma utilizing a standard step-wise approach. First choose the child’s age and then ask questions pertaining to the impairment/risk. Based on this you will be given a “step”. The appropriate treatment for each step is outlined a table you will view shortly.

Stepwise Approach for Classifying Asthma Severity (9)

AGE | COMPONENTS OF SEVERITY | INTERMITTENT | MILD PERSISTENT | MODERATE PERSISTENT | SEVERE PERSISTENT | |

0-4 years | Impairment | Symptoms | ≤2 days/week | >2 days/week but not daily | Daily | Throughout the day |

Nighttime awakenings | 0 | 1-2x/month | 3-4x/month | >1x/week | ||

SABA use | ≤2days/week | >2 days/week but not daily | Daily | Several times per day | ||

Interference with normal activity | None | Minor limitation | Some limitation | Extremely limited | ||

Risk | Exacerbation requiring oral systemic corticosteroids | 0-1/year | ≥2 exacerbations in 6 months requiring oral systemic steroids or ≥4 wheezing episodes/1 year lasting >1 day and risk factors for persistent asthma | |||

Management | Recommended step therapy | Step 1 | Step 2 | Step 3 plus consider short course of oral systemic corticosteroids | ||

5-11 years | Impairment | Symptoms | ≤2 days/week | >2 days/week but not daily | Daily | Throughout the day |

Nighttime awakenings | ≤2days/month | 3-4x/month | >1x/week but not nightly | Often 7x/week | ||

SABA use | ≤2days/week | >2 days/week but not daily | Daily | Several times per day | ||

Interference with normal activity | None | Minor limitation | Some limitation | Extremely limited | ||

Lung Function | Normal FEV1 between exacerbations FEV1 >80% predicted FEV1/FVC >85% | FEV1 = >80% predicted FEV1/FVC >80% | FEV1 = >60%-80% predicted FEV1/FVC 75%-80% | FEV1 = <60% predicted FEV1/FVC <75% | ||

Risk | Exacerbation requiring oral systemic corticosteroids | 0-1/year | ≥2 per year. Consider time since last exacerbation as frequency and severity may change overtime. | |||

Management | Recommended step therapy | Step 1 | Step 2 | Step 3, medium-dose ICS option and consider short course of oral systemic corticosteroids | Step 3 medium-dose option, or Step 4 and consider short course of oral systemic corticosteroids | |

≥12 years | Impairment | Symptoms | ≤2 days/week | >2 days/week but not daily | Daily | Throughout the day |

Nighttime awakenings | ≤2days/month | 3-4x/month | >1x/week but not nightly | Often 7x/week | ||

SABA use | ≤2days/week | >2 days/week but not daily, and not more than 1 time on any day | Daily | Several times per day | ||

Interference with normal activity | None | Minor limitation | Some limitation | Extremely limited | ||

Lung Function | Normal FEV1 between exacerbations FEV1 >80% predicted FEV1/FVC normal | FEV1 >80% predicted FEV1/FVC normal | FEV1 = >60% but <80% predicted FEV1/FVC reduced by 5% | FEV1 = <60% predicted FEV1/FVC reduced by >5% | ||

Risk | Exacerbation requiring oral systemic corticosteroids | 0-1/year | ≥2 per year. Consider time since last exacerbation as frequency and severity may change overtime. | |||

Management | Recommended step therapy | Step 1 | Step 2 | Step 3 and consider short course of oral systemic corticosteroids | Step 4 or Step 5 and consider short course of oral systemic corticosteroids | |

Asthma Therapies

Asthma is treated in a stepwise approach based on asthma symptom severity. Using the stepwise approach allows providers to prescribe appropriate medications for each child in order to optimizing symptom control.

A review of common asthma medications and their escalation of prescription based on the stepwise approach are listed below.

Stepwise approach for pharmacologic management of asthma (9)

AGE | STEP 1 | STEP 2 | STEP 3 | STEP 4 | STEP 5 | STEP 6 |

| 0-4 years | SABA PRN | Preferred: Low-dose ICS Alternative: Cromolyn or montelukast | Preferred: Medium-dose ICS | Preferred: Medium-dose ICS plus either LABA or montelukast | Preferred: High-dose ICS plus either LABA or montelukast | Preferred: High-dose ICS plus either LABA or montelukast plus consider oral systemic corticosteroid |

| 5-11 years | SABA PRN | Preferred: Low-dose ICS Alternative: Cromolyn, LTRA, nedocromil, or theophylline | Preferred: Low-dose ICS plus either LABA, LTRA, or theophylline Alternative: Medium-dose ICS | Preferred: Medium-dose ICS plus LABA Alternative: Medium-dose ICS plus either LTRA or theophylline | Preferred: High-dose ICS plus LABA Alternative: High-dose ICS plus either LTRA or theophylline | Preferred: High-dose ICS plus LABA plus oral systemic corticosteroid Alternative: High-dose ICS plus either LTRA or theophylline plus oral systemic corticosteroid |

| ≥12 years | SABA PRN | Preferred: Low-dose ICS Alternative: Cromolyn, LTRA, nedocromil, or theophylline | Preferred: Low-dose ICS plus either LABA or Medium-dose ICS Alternative: Low-dose ICS plus either LTRA, theophylline or zileuton | Preferred: Medium-dose ICS plus LABA Alternative: Medium-dose ICS plus either LTRA, theophylline or zileuton | Preferred: High-dose ICS plus LABA AND consider omalizumab for patients with allergies | Preferred: High-dose ICS plus LABA plus oral corticosteroid AND consider omalizumab for patients with allergies |

Medications

Inhaled Short-Acting Beta2-Agonists (SABA):

SABA medications are the preferred therapy in the event of acute asthma symptoms, asthma exacerbations, and in preventing exercise-induced asthma symptoms (taken before the activity). Albuterol, Levalbuterol, and Pirbuterol relax airway smooth muscles within minutes to allow relief of inflammation and improvement of airflow.

Children with intermittent asthma may not require a daily, preventative medication. They may only be prescribed a SABA medication for acute symptom exacerbation. Frequency of SABA medication use can be an indicator of asthma activity and control.

Using a SABA medication greater than two days a week for symptom relief generally indicates suboptimal control and indication to move up a treatment step. Of note, all children with asthma are prescribed a SABA medication to use as a rescue, quick-relief medication. (9)

Inhaled Corticosteroids (ICS):

Inhaled Corticosteroids work by suppressing cytokine involvement, decreasing the involvement of the airway’s eosinophil cells and preventing an increase in inflammatory mediators. Use of long-term ICS can prevent the need for oral systemic steroid administration by controlling asthma symptoms. Variable dosing of ICS medication is used depending on severity and persistence of asthma symptoms.

Side effects in long-term use include impaired growth in children, decreased bone mineral density, skin thinning and bruising, and cataracts. Children on this medication should be instructed to use a spacer (if applicable) and rinse their mouths after inhalation to prevent oral thrush. Common ICS medications include Fluticasone (Flovent HFA), Budesonide (Pulmicort Flexhaler), Mometasone (Asmanex Twisthaler), Beclomethasone (Qvar RediHaler), and Ciclesonide (Alvesco) (9)

Cromolyn Sodium and Nedocromil:

Cromolyn sodium and nedocromil are alternative treatment options to low-dose ICS for mild persistent asthma and exercise-induced asthma. These medications are generally not preferred in children. Studies have shown inconclusive results to the impact of effectiveness of this medication in children. (9)

Leukotriene modifiers (LTRA):

Leukotriene modifiers may be used as an alternate treatment option for mild persistent asthma and step 2 of asthma management. They are not recommended over LABA medications in ages >12 years. These medications work by preventing the release of mast cells, eosinophil cells, and basophils that cause airway constriction, vascular permeability, and increased mucous.

Medications in this class include Montelukast, Zafirlukast, and Zileuton. Montelukast can be prescribed in children over the age of 1 and Zafirlukast for children over the age of 7. Zileuton is currently not approved for use in children. (9)

Methylxanthines:

Theophylline is a methylxanthine that can be used as an alternative or adjunctive therapy to ICS for mild persistent asthma in children older than 5. In previous trials, theophylline was shown to have little effect on airway reactivity and produced significantly less control than the use of low-dose ICS alone (9). Because of this and it’s narrow margin of safety, it’s use has largely fallen out of favor.

Inhaled Long-Acting Beta2-Agonists (LABA):

LABA medications stimulate the beta2-receptors to relax the smooth airway muscles. They are the preferred medication to be used in adjunct with ICS medications. They are not recommended alone and not recommended to treat acute asthma symptom exacerbation. LABA therapy should be considered in children ages 5+ who are not well controlled on ICS management alone. The LABA medications on the market today are Salmeterol and Formoterol. (9)

Oral Systemic Corticosteroids:

Oral corticosteroids are usually reserved for severe asthma flares or in the event of difficult-to-control asthma. Side effects such as adrenal suppression, growth suppression, dermal thinning, hypertension, Cushing’s syndrome, cataracts, and muscle weakness may occur and are more likely with chronic usage. If oral corticosteroids are being used more than three times a year for management of asthma exacerbations, reevaluation of long-term asthma control should be evaluated.

Experimental Treatments

Immunomodulators:

Immunotherapy for asthma management is a relatively new concept. Research is currently being performed to address and assess the effectiveness of immunotherapy in preventing asthma symptoms.

Some therapy modules being studied include Omalizumab, Methotrexate, Soluble interleukin-4 receptor, anti-IL-5, recombinant IL-12, cyclosporin A, intravenous immunoglobulin (IVIG), and clarithromycin. (9)

Complementary and Alternative Medicine (CAM):

Many CAM therapies have not been proven to statistically to reduce asthma incidence, severity, or risk. Practicing alternative medicine strategies is not recommended as a replacement to scientifically proven pharmacologic management, but they may be used as an adjunct if appropriate.

These therapies include acupuncture, chiropractic therapy, homeopathic and herbal medicine, breathing techniques, relaxation techniques, and yoga. (9)

Learner exercise

There are a myriad of treatment options for pediatric patients with asthma. What are the first-line treatments?

What are some of the side effects of long term systemic corticosteroid administration? Are these risks the same for inhaled steroids?

Some patients wish to incorporate CAM therapies. How will you approach this? What kind of education would you provide on this subject?

Asthma Prevention Strategies

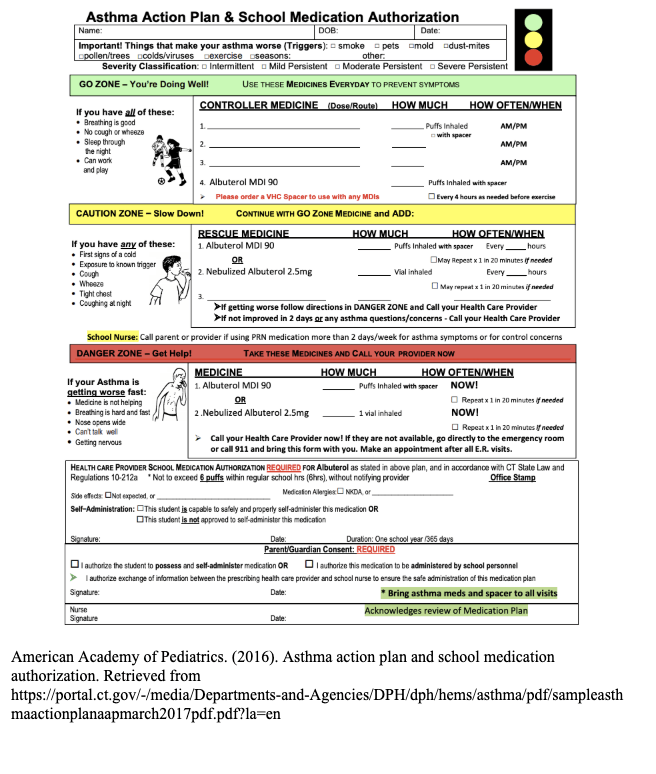

Asthma Action Plan:

The Asthma Action Plan (1) is a great tool for families. It can improve recognition of the early signs of asthma exacerbations and facilitate appropriate treatment of asthma symptoms. It was found in the NCHS’s National Health Interview Survey performed in 2016, that only 50.8% of children reported they had received asthma actions plans and only 76% were taught how to recognize early signs of an asthma attack (12). If updated frequently with the child’s healthcare provider and followed in the event of asthma symptoms it may reduce exacerbation severity and duration, primary care office visits, hospital visits, and asthma-related deaths (1).

Asthma action plans are designed to provide families one place to collect all the child’s critical information regarding their asthma including: name, date of birth, current medications for long-term maintenance, quick-relief medications, medication dosing/instructions, and important phone numbers in case of emergency. This information helps guide caregivers to act quickly when exacerbations occur. It also identifies common asthma symptoms that might be overlooked and plans appropriate treatment steps to complete in the event these symptoms occur.

There are three zones on the Asthma Action Plan: green, yellow, and red. Each zone indicates increasing severity of symptoms and identifies appropriate treatments or interventions. With proper control of their asthma disorder, children and adults alike should spend a majority of their days in the green zone. This zone indicates that there are no asthma symptoms, even in play or activity (1). Prevention of trigger exposure is the key to maintaining this zone.

The next zone, yellow, indicates that the child is not feeling well and is experiencing asthma symptoms such as coughing, wheezing, runny nose/cold symptoms, breathing harder or faster, waking at night coughing, and playing less than usual (1).

The final zone, red, indicates the danger zone in which the child’s symptoms worsen so drastically that in addition to giving the medications listed on the plan, taking the child immediately to the hospital or calling 9-1-1 is the necessary course of action (1).

Some children, even if they spend the majority of their days in the green zone, can quickly escalate to the red zone. Educating families on this plan is critical to helping them make the best decisions for their children in both preventing and managing asthma symptoms.

Controlling Allergies and Environmental Triggers

Children with asthma often lead normal lives until a trigger initiates the inflammatory cascade resulting in an asthma exacerbation. Up to 90% of children with asthma symptoms also have allergies (11). Some of the most common allergens and environmental triggers for asthma, both indoor and outdoor, include dust mites, molds, trees or pollens, cockroaches, pet dander, secondhand smoke, ozone, and particle pollution (7,11).

Exercise and stress can also be triggers for asthma symptoms (10). While limiting exercise is not generally recommended unless prescribed by a healthcare provider, choosing less physically demanding exercises may result in better asthma control. Children with well-controlled asthma are often able to complete activities and exercise as desired (10).

Teaching families how to identify asthma triggers and avoid the child’s exposure when possible can significantly reduce asthmatic complications. Below are a few suggestions that can be offered to families to help improve environments for children with asthma.

Avoiding Common Asthma Triggers (2,7,9):

- Frequently wash hands to avoid spread of infection (common cold, alternate viruses, bacteria).

- Close house windows, doors, and car windows to prevent increased exposure to pollens and other outdoor allergens

- Use zippered mattress and pillow covers to reduce exposure to dust mites.

- After playing outside, immediately change clothes and/or bathe to reduce prolonged exposure to outdoor allergens.

- If possible, remove old carpeting and/or frequently vacuum when child is not around.

- Avoid humidifiers that may harbor mold and bacteria.

- Monitor for food allergies including but not limited to milk, eggs, peanuts, tree nuts, soy, wheat, fish, shellfish, and food additives.

- Address pets in the home. If pets are an asthma trigger and rehoming is not an option, bathe pets weekly, keep them outside as much as possible, and avoid having them in child’s bedroom.

- Avoid secondhand smoke. Ask those who smoke to not smoke around the child, smoke in designated rooms, or cease smoking all together.

These interventions, along with providing thorough asthma prevention and treatment education to families have been proven to significantly reduce complications from asthma (12).

Peak Flow Meters

Peak flow meters are small, hand-held devices used to measure exhaled airflow (2). In the event of an asthma exacerbation, airways become inflamed, trapping air in the lungs and increasing the difficulty of proper exhalation. The use of the peak flow meter can help identify narrowing of the airway prior to the actual presence of asthma symptoms (2).

In the National Health Interview Survey (NHIS) performed in 2016, reports determined that only 50.6% of children were taught how to use a peak flow meter (12). Using the peak flow meter presents an opportunity treat early signs of asthma exacerbations with the hope of ultimately reducing the incidence of moderate to severe symptoms.

Peak flow meter education may seem intimidating to families at first. However, it is quite simple. Just like the Asthma Action Plan, peak flow meters have three zones that indicate severity of airway inflammation. The green zone is considered the safe zone, yellow is the caution zone, and red is the emergency zone (2). Each zone indicates a percentage of the child’s personal best exhaled air flow.

The green zone indicates 80-100% of the child’s personal best flow; the yellow zone measures 50 to less than 80%; and the red zone measured less than 50% of the child’s personal best flow. (9) Using the results of the peak flow meter test with the asthma action plan can help families decide the appropriate course of action in asthma management.

To use the peak flow meter, the child should move the marker on the meter to zero, sit or stand-up straight, take a deep breath, put the meter into the mouth closing the lips around the mouthpiece, and blow as hard and fast as possible (9). The number noted on the meter should then be marked in a log and the steps repeated 5-6 more times (9).

The best three numbers should then be recorded in a final log to determine how well the child’s asthma is controlled. Families should be instructed to record a log over the course of a couple weeks to determine the child’s best peak flow rate as well as determine the colored zones for future asthma management.

After the zones are created with the data collected, the child should then use the peak flow meter daily, to determine if the child is experiencing airway inflammation. The child and family should use the results to compare to the treatment plan as written on the child’s asthma action plan (2,9).

Learner exercise

What age-appropriate interventions can you use to ensure that patients properly utilize their inhalers and peak flow meters?

For example how would you approach a toddler in comparison to an adolescent?

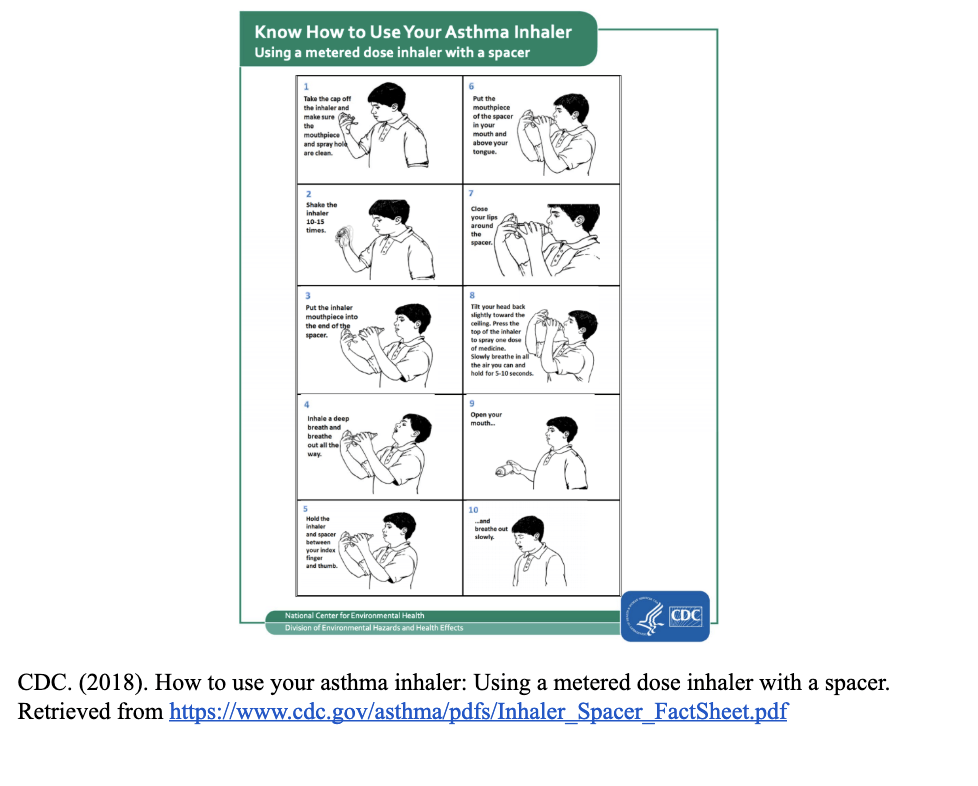

Proper Medication Administration

Proper medication administration is crucial to asthma control. It is no longer recommended to use inhaled medications without the use of a spacer (4). A spacer device helps deliver doses of inhaled medication in a more streamlined and coordinated movement (4).

However, despite being taught how to properly use a spacer upon prescription of an inhaled medication, many children and families forget to use or improperly use the device. Spacer use and proper medication administration should be reviewed with every child and their family at all asthma related healthcare appointments and/or emergency department visits.

Ensuring that children and families are using medications correctly may reduce and even prevent serious asthma exacerbations in the future.

Summary

Summary

Asthma is a prevalent, chronic illness in society. Understanding the disease process, therapy options, and promoting prevention strategies can help manage this chronic disease- reducing complications and improving quality of life.

Online resources offered through national organizations, such as the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, American Academy of Pediatrics, Healthy People 2020, the Asthma and Allergy Foundation of America provide excellent information for both patients and healthcare members.

It has been said that an ounce of prevention is worth a pound of cure. This holds true for asthma even more so than many other diseases. Focusing on prevention strategies, proper and prompt treatment, and appropriate use of resources are the cornerstone of asthma treatment.

Case Study

A father and his 5-year-old son present to the primary care office: The father states that the child has been coughing at night 2-4 nights a week; coughing every morning; and has difficulty breathing with exercise or exertion. The child experienced a cold a few weeks ago and since then, the coughing has not improved.

The father denies any fever. He describes the coughing as hoarse, hollow, dry, and sometimes barky. The child also frequently experiences rhinorrhea and increased sputum, but father denies those symptoms at present. The father mentions that they have been to the emergency department twice in the past 6 months for similar symptoms and the child has received two treatments of nebulized Albuterol (2.5mg) at each visit.

They were not sent home with any medications. Father states that while the Albuterol treatments in the emergency department helped for a couple days, the coughing would return. The family has one dog in the home and the child frequently spends time at his grandparents’ house where he is exposed to secondhand smoke.

The child appears healthy in clinic today. His vital signs read: O2: 100%, Respiratory Rate: 13, Heart Rate: 119, Blood Pressure: 97/62, and Temperature: 98.2F. He is sitting comfortably in the office but will frequently clear this throat and have a harsh cough. Upon listening to the child’s lungs, wheezes are noted bilaterally in the bases. There are no retractions, rhonchi or rales.

The healthcare provider performs spirometry testing to evaluate the child’s lung compliance and level of obstruction prior to administering a SABA medication. After completing the spirometry, the child is noted to have a FEV1 75% of predicated value. A nebulized Albuterol treatment is completed and the child performs the spirometry again. After the treatment, the child’s FEV1 returns to a normal range >85% of predicted value.

Physical exam reveals improvement in wheezing and the child states he can breathe better. Based on the child’s history of persistent coughing >2 nights a week, coughing every morning, limitations on activity due to respiratory symptoms, and an initial abnormal FEV1 (though resolved after SABA administration), the healthcare provider determines that the child has Mild-Persistent Asthma.

Based on the step-wise approach of managing asthma, the child is treated as a Step 2 for symptoms aligning with mild-persistent asthma disease. The healthcare provider prescribes the child a rescue Albuterol inhaler (SABA) and long-term, low-dose Fluticasone (Flovent HFA) inhaler (ICS). The healthcare provider recommends to the father that the child be tested for allergies to help identify possible triggers to asthma symptoms. If the child is found to have significant allergies, an additional allergy medication may be prescribed at that time.

The father and child are educated on proper administration of the medications with use of a spacer and given a peak flow meter to measure the child’s exhaled airflow. The father is instructed on how to find the child’s best peak flow rate over the next two weeks and use that to determine critical values of expected airflow. The child should continue to record the peak flow measurements daily to assess early changes in airway obstruction.

The healthcare provider then develops an Asthma Action Plan with the father and child to provide a guideline of therapy, write important medication and emergency information, and help to identify early asthma symptoms and emergency treatments.

They discuss common asthma triggers to avoid. The father and child are encouraged to keep their pets out of the child’s room as much as possible and outside whenever feasible. The child should use a zippered mattress and pillow protector to prevent exposure to dust mites and flooring should be mopped or vacuumed frequently while the child is outside of the home.

It is also recommended that secondhand smoke exposure is limited by way of having grandparents smoke outside of the home, see the child at his home where there is less smoke, and change their clothes or use a smoking jacket that can be removed after smoking before being with the child.

With new information in hand, the father and child, while overwhelmed, feel they can start to prevent and treat the child’s asthma symptoms. The family should be encouraged to follow-up closely with their primary healthcare provider to ensure appropriate control and reduce chronic airway inflammation.

Not a member? Sign up here to complete the course and receive your certificate.

References (Bibliography)

(1) American Academy of Pediatrics. (2016). Asthma action plan and school medication authorization. Retrieved from https://portal.ct.gov/-/media/Departments-and-Agencies/DPH/dph/hems/asthma/pdf/sampleasthmaactionplanaapmarch2017pdf.pdf?la=en

(2) Asthma and Allergy Foundation of America. (2015). Preventing asthma episodes and controlling your asthma. Retrieved from https://www.aafa.org/asthma-prevention/

(3) CDC. (2015). Asthma: Asthma-related missed school days among children aged 5-17 years. Retrieved from https://www.cdc.gov/asthma/asthma_stats/missing_days.htm

(4) CDC. (2018). Asthma: Know how to use your asthma inhaler. Retrieved from https://www.cdc.gov/asthma/inhaler_video/default.htm

(5) CDC. (2018). Asthma: Most recent asthma data. Retrieved from https://www.cdc.gov/asthma/most_recent_data.htm

(6) CDC. (2015). Asthma severity among children with current asthma. Retrieved from https://www.cdc.gov/asthma/asthma_stats/severity_child.htm

(7) CDC. (2018). Home characteristics and asthma triggers: Checklist for home visitors. Retrieved from https://www.cdc.gov/asthma/pdfs/home_assess_checklist_P.pdf

(8) Hsu J, Sircar K, Herman E, Garbe P. (2018). EXHALE: A technical package to control asthma. Atlanta, GA: National Center for Environmental Health Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

(9) National Asthma Education and Prevention Program. Expert Panel Report 3: Guidelines for the Diagnosis and Management of Asthma. (2007). NIH Publication 07-4051. Bethesda, MD: National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute. Retrieved from http://www.nhlbi.nih.gov/guidelines/asthma/

(10) Schuers, M., Chapron, A., Guihard, H., Bouchez, T., & Darmon, D. (2019). Impact of non-drug therapies on asthma control: A systematic review of the literature. European Journal of General Practice. doi: 10.1080/13814788.2019.1574742

(11) United States Environmental Protection Agency. (2016). Asthma facts. Retrieved from https://www.epa.gov/sites/production/files/2016-05/documents/asthma_fact_sheet_english_05_2016.pdf

(12) Zahran, H., Bailey, C., Damon, S., Garbe, P. & Breysse, P. (2018). Vital signs: Asthma in children — United States, 2001–2016. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.15585/mmwr.mm6705e1

Disclaimer

Use of Course Content. The courses provided by NCC are based on industry knowledge and input from professional nurses, experts, practitioners, and other individuals and institutions. The information presented in this course is intended solely for the use of healthcare professionals taking this course, for credit, from NCC. The information is designed to assist healthcare professionals, including nurses, in addressing issues associated with healthcare. The information provided in this course is general in nature and is not designed to address any specific situation. This publication in no way absolves facilities of their responsibility for the appropriate orientation of healthcare professionals. Hospitals or other organizations using this publication as a part of their own orientation processes should review the contents of this publication to ensure accuracy and compliance before using this publication. Knowledge, procedures or insight gained from the Student in the course of taking classes provided by NCC may be used at the Student’s discretion during their course of work or otherwise in a professional capacity. The Student understands and agrees that NCC shall not be held liable for any acts, errors, advice or omissions provided by the Student based on knowledge or advice acquired by NCC. The Student is solely responsible for his/her own actions, even if information and/or education was acquired from a NCC course pertaining to that action or actions. By clicking “complete” you are agreeing to these terms of use.